The earliest settlements in the Bursa region date back to the Chalcolitic, late Chalcolitic and early Bronze ages (5000-2000 BC). Unfortunately, systematic excavations that might throw light on the prehistoric periods have not yet been iniated. The written story of the region starts with the Aegean migrations, which affected all of western Anatolia from the mid 2000s onwards. Among the peoples that came in waves from Thrace toAnatolia were the Bithyni and Thyni, who settled in the Bursa, izmit and Bilecik regions, and for a long time, begining from antiquity, the region was named Bithynia after them. During the period of the Hellenistic Kingdoms following Alexander’s death, a Bithynian kingdom was founded, and remained sovereign until 71 BC when the whole region came under Roman rule. It is highly probable that the foundation of Bursa, or Prusa, as it was known in ancient times, was laid under the Bithynian King Zipoites (326-279 BC) but the city as we now know it was erected under Prusias I (232-192) BC and was named after him.When the Roman Empire was divided, Bithynia remained under the rule of Byzanthium. Prusa developed and flourished during this time and became world-famous with its hot springs. In 1326 Bursa was captured by the Ottomans and enjoyed the most magnificient period of its history. It was the first capital of the young Ottoman State.During this period which ended with the conquest of istanbul, Bursa was adorned by several lovely buildings.

The first six Ottoman Sultans before Murat II were buried in Bursa, in the complexes bearing their names. Bursa suffered great destruction because of a fire within the citadel and an earthquake in 1855 but the city was quickly reconstructed according to the old plan.After the first world war, recovered its fast pace of development under the Republic and has thus evolved into the rich, vivid, and modern Bursa of today...

Bursa's Market Area

The original covered bazaar and the bedesten was originally built in the late 1300s by Sultan Yildirim Beyazit, but the earthquake of 1855 and after that the big fire in 1958 gave great damage and brought it down. The reconstructed old parts of the bazaar such as the Bedesten retains the look and feel of the original, though it is obviously much tidier. This is not a tourist trap really; most of the shoppers are local people. As you wander around the covered bazaar, look for the "Eski Aynali Carsi" which, though now a market, was originally built as the Orhangazi Hamami (1335), the Turkish bath of the Orhan mosque külliyesi (complex). The domed ceiling with many small lights shows this...

In Eski Aynali Carsi is a shop called Karagöz open daily except Sunday and run by a man called Sinasi Celikkol and his son Ugur Celikkol. Sinasi specializes in quality goods-copper and brass, carpets and kilims, knitted gloves and embroideries, old and new jewellery etc.- at fair prices, as did his father Rafet before him. It is the oldest store of the town whereas some others have taken their place in the same market. This is the place to find the delightful Karagöz Shadow puppets. Cut from flat, dried camel leather, painted in bright colours, and oiled them to make translucent, the puppets are an authentic Turkish craft item. Sinasi Bey periodically organises performances of the shadow plays, if you're interested, ask at the shop about the next shows. If one is not scheduled, he may give you a brief idea of how the shadow-puppet theatre works right in his shop... Don't forget to visit the Koza Han or Silk Cocoon Caravanserai, just otside the Bedesten's eastern entrance, built in 1490 and lively with cocoon dealers in june and also in september when there is a second harvest. Another place you ought to visit in the Bedesten is Emir Han, adjoining the north east corner of the Ulu Cami, a caravanserai used by many of Bursa's silk brokers today as it has been for centuries...An interesting experience for you, stroll around the Bursa's covered Bazaar and the market area and discover more

Turkish Art in Bursa and Environs

A full, large-scale study of Turkish art history that comprehends the entire development of Turkish art from earliest times to the present has yet to be written. Research and studies on the traces left by Turkish settlement and civilizations would incorporate all stages of Turkish art, its origins, the sources of inspiration, foreign influences to which it was subjected and the influence it exerted on other milieus. Chronologically, the Ottoman Turkish civilization is the closest to us among the ancient Turkish civilizations. We see its heritage in our country all around us and it lives in us and among us; and it is perhaps for this reason that we fail to assign to it the value it deserves; and, consequently, we give our tacit assent to its state of neglect and its disappearance. The arts and architecture as well as the decorative arts and minor arts and the various branches of monumental art of the Ottomans, who succeeded the Seljuks and which was the second greatest Turkish civilization in Anatolia, exhibit a variety of characteristics. Differences in the character of the taste, style, tradition and evolution displayed by both large and small works of art that were created by the same community of people are evident. The works of Ottoman Turkish civilization around us and among which we live fail to a great extent to attract our attention; yet, they possess a great signifıcance as the fınal and most developed link in the chain of Turkish art. It is an undeniable truth that Turkish art, whose traces we are able to follow in various countries since the Turks left Central Asia, rapidly attained the last and most perfect solutions with an astonishing success and evolutionary pace in the Ottoman period. Hence, Bursa-as the nucleus of this civilization that spread throughout the Mediterranean basin by developing swiftly within a brief period-commands an importance of the highest degree.As the possessor of radically different qualities as an art that the Turkish arts of former eras, the environs of Bursa is an area that possesses a brand new perspective, an entirely new aesthetic and an unprecedented understanding according to which the works evolved. All kinds of early works, both large and small, in Bursa and vicinity represent the fırst sparks of the greatest brilliance of Turkish art. Bursa, as one of the great centers of art of the Turkish civilization, constitutes the basic nucleus of this preparatory phase; the towns in the area with the works contained in them complement it, so that Bursa represents a whole from the perspective of art history. The structures in Yenişehir and İnegöl and those in Bursa closely resemble each other Just as one may trace the intervening stages of the rapid development of Ottoman Turkish art in them, one may also ascertain in them the existing distinctions from the previous Seljuk art. In short, Bursa and its surrounding area is a region of the historical current of Turkish art that has drawn the most attention .

Works deriving from the Byzantine period may be encountered at various sites in Bursa and its nearby districts. Apolyont Lake is one such locale as is Mudanya, near which is found the old Byzantine Church of St Stephen at Tirilya, now known as Zeytinbağı near Mudanya. But, the most notable Byzantine remains can be found in İznik (ancient Nicaea). The city walls of İznik and the later Mosque of Orhan which was formerly the Church of St. Sophia, now standing in ruins, are the most characteristic works here. These and other relics of the same period in the region are important especially because of the opportunity for comparison they represent in demonstrating differences with Turkish construction art. Almost all traces that would show that Bursa was at one time a strong, medieval Christian city have vanished.

A round, ecclesiastical structure whose original name was Mikael and is incorrectly known as the Church of Elijah was extant up to the middle of the past century. This eminent lone survivor in Bursa of the Byzantine period, which because of the brightness of the reflection of light from its roof covering was renowned as the Silver (Gümüşlü) Dome; in accordance with the terms of his will, Osman Gazi, who impatiently awaited news of the conquest of Bursa, was buried here by his son Orhan Gazi. Unfortunately the present form of the Tomb of Osman Gazi was constructed in the second half of the last century following the earthquake of 1855 is rather recent.Bursa was adorned by magnifıcent architectural works, beginning with its conquest by the Turks; and within a short time the art of Turkish construction was represented by new discoveries in a variety of types. Foremost among those on which we must dwell is an important work of art, the Ulu (Great) mosque. This grand monument embodied the principles of Turkish urban concepts of that period. In every Turkish city, a great mosque that usually can accommodate the entire male population of the town holds the position of being the main mosque. But the Ulu mosque of Bursa occupies quite a distinctive position due to the architectural resemblances of those in a number of cities and towns of Anatolia. The starting point here is the principles that dominate in the other similar examples and whose origins lie in very ancient Islamic places of worship, yet, this traditional form has been bonded to a new appearance. Portions of the early great mosques that were set apart by columns and pillars where prayers were performed and the flat roof or other vaulted coverings have here been abandoned; in their stead are a series of extraordinarily heavy pillars and twenty domes of equal size. The act of opening one of these domes and the situating of a fountain for ablutions beneath it are remarkable for its genuine continuation of the traditional pillared and open courtyard mosque. Another example where the same principle has been applied in a more minor fashion is the Molla Arap mosque. According to the existing inscription of the Şehadet mosque in the citadel-which seems to derive from the reign of Orhan, but which gives rise to certain doubts on this subject-is another example of the great mosque type. In the event that it actually belongs to the period of Orhan, this mosque would represent the earliest important example of a Turkish work. Very unfortunately, it was greatly damaged in the earthquake of 1 855 and, towards the end of the last century, with the loss of its two side units, it assumed this form. Today this structure is covered by two domes.

The Orhan mosque, the Hüdavendigâr mosque of Murad I, the Yıldırım Beyazıd mosque, the renowned Green mosque and the Muradiye mosque at Bursa possess a different form; an architectural form that represents several other mosques whose origins carry a direct tie to the native lands of the Turks. This type has a courtyard covered by a dome, which is followed by a second space where prayers are held; on either side of which are cloister cells (tabhâne) that open onto the first domed space. It is clear that these structures, which are related to the wandering dervishes who played a very prominent role in the earliest foundation phase of the Ottoman state, are nothing other than dervish lodges that were assigned to them. But, from the sixteenth century onwards, this institution strayed far from its fundamental objectives; and after it had completely altered its essence, this kind of cloister-cell mosque assumed the character of an ordinary neighborhood mosque. One may fınd examples signalling the various stages of development of the same form in the Nilüfer Hatun soup kitchen in İznik and the Yakup Çelebi dervish lodge in İznik, the Baba Sultan dervish lodge in Yenişehir the İshak Pasha mosque and the Karacabey mosque in İnegöl.

It is very diffıcult to delineate in a few sentences like this how rich and what a variety of appearances were sought by Turkish art in Bursa and environs. This fairly small area, which from the perspective of chronology has very narrow limits, is so filled with such a number of varied and innovative examples, that it is impossible not wonder at the masters who took lessons from the rich cultures, creative geniuses and experience of the artists who contributed innovations to this art during this period of Turkish art. One of the earliest Ottoman Turkish works with an inscription is the Hacı Özbek mosque-unfortunately, ruined by very poor repairs of recent date-dated to 1333 (734 H.) in İznik; it is a simple, plain and modest structure comprised of a rectangular prayer space covered by a single dome. There is no need to go afar in order to see what a magnifıcent result was achieved in a very short time with this unassuming form, which had just previously been utilized by the Seljuks in similar but hesitant forms in the earliest examples and which, at fırst glance, seems too simple to allow for architectural possibilities. The Green mosque also in İznik by the architect Mimar Hacı Musa between 1378-91 (780-94 H.), which was mercilessly put in a ruined state during the War of Liberation in the early years of this century, survives as a masterpiece of Turkish art and a magnifıcent example of this type. The Green mosque with its minaret bonded with green and purple glazed bricks, an ancient Turkish tradition; marble facade carved like lace; simple, single-domed interior space divided by double columns, an excellent discovery that enlarges the interior and set apart the worship space is, without a doubt, a thoroughly Turkish work and an example of a developed phase of a new architectural form. A short tour of the streets of Bursa will suffıciently demonstrate what kinds of solutions were achieve by Turkish architecture in the small neighborhood mosques composed of similar single spaces. The Tımurtaş mosque, the Abdal Mehmed mosque, the Aynalı mosque, which has a special beauty bestowed by the minaret that rises over the ablution fountain, and the Salt Market mosque which possesses wonderful brick decoration and others are all-small but valuable-historical and artis- tic monuments of the early Ottoman period.

The importance and value of this area from an art historical view is not composed entirely of mosques. The early great names of the Ottoman state and their tombs are each one an historical and artistic monument. Similarly at Söğüt, the tomb of Ertuğrul Gazi, those of Murad I Hüdavendigâr Yıldırım Beyazıd, Mehmet I, Murad II and Musa Çelebi and Cem Sultan and numerous tombs of princes may be pointed out as prominent examples in Bursa. The tombs of Karacabey and İshak Pasha in İnegöl, Lala Şahin at Kemalpasha and the entire Candarlılar family in İznik are definite hallmarks of Turkish history. Unfortunately, the tombs of Osman Gazi and Orhan Gazi at Bursa suffered a complete loss of their original forms due to recon-struction in the last century. Besides these tombs which eternalize great historical personalities, there are also tombs associated with a groups of semi-legendary individuals; for example, the tomb of Sarı Saltuk at İznik is one of these. It is composed of a small dome supported by four pillars on which rest four vaults. Bursa and its countryside is embellished not only by the graves of well-known great personages, but it may be regarded as a center exhibiting the greatest variety of examples of decorative Turkish art as well as beautiful specimens of Turkish calligraphy. Sad to say, due to the effects of strange attitudes in recent years, beautiful, centuries-old trees in the cemeteries have been cut down and the stones of grave monuments-each one a marvellous work of art-have been broken. A great proportion of the grave- stones have been removed to the courtyard of Muradiye mosque where they have been lined up in military order Nevertheless, some attractive examples remain. Perhaps the least known, but the most noteworthy examples of the Turkish grave monuments eternalizing the dead without making the unloveliness of death perceptible, are without a doubt the ancient Se Juk gravestones deriving from the brief period of Seljuk rule of İznik between 1081-97. These grave stones that were later re-used by the Byzantines in the construction of the citadel are remarkable for their antiquity, their modest appearing inscriptions and especially their forms, which recall ancient Greek sarcophagi.

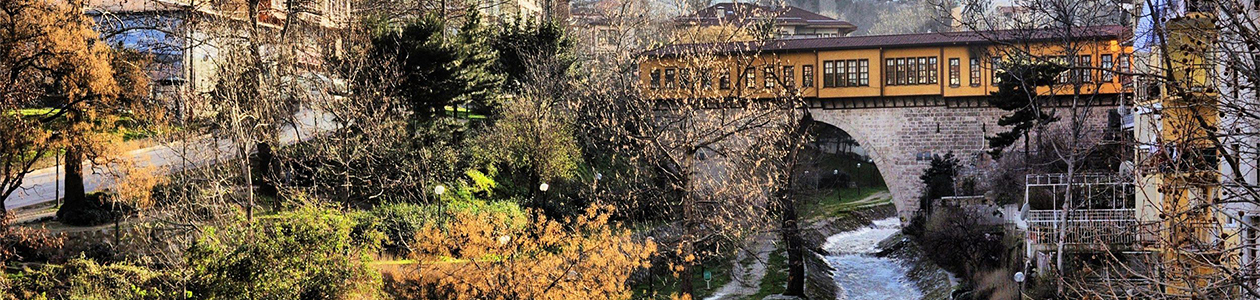

From the spiritual side, the Turkicization movement of Western Anatolia was careful to spread its civilization by founding strong cultural centers in the fourteenth century to reinforce itself. Regrettably, no remains are extant of the madrasa founded by Orhan in İznik, conquered in 1330, to which were appointed well-known scholars of the day. But, Süleyman Pasha madrasa, also in İznik, one of the oldest Ottoman madrasas and which lay for years in a state of ruins has been restored. The madrasas that were constructed, primarily next to mosques, in Bursa-which was one of the greatest cultural centers prior to Edirne and, particularly before Istanbul-are, in addition to their artistic qualities, possessors to a great degree of the history of Turkish civilization as living memories. The madrasa of Mehmed I (built as an annex to the Green mosque), whose classroom housed for a time the Bursa museum, which is domed but, conforming to ancient tradition, opens onto the courtyard as an arch in the form of an eywan; in addition, the madrasas of Murad I Hüdavendigâr and Yıldırım Beyazıd may also be included among the most monumental examples. The madrasa in the mosque of Murad I Hüdavendigâr whose character is unique in Turkish art, is not a separate building; rather the mosque and the dervish lodge are gathered under one roof and the madrasa cells are arranged on the second storey of the structure. This very unusual form of mosque which was never repeated in Turkish art resulted in a facade that is unique in Turkish art. In the Turkish art of facade architecture in the Mediterranean basin and in that of Byzantine works in the fourteenth century; Turkish elements are being employed. In all the cities becoming Turkicized-with Bursa the most prominent-a great many buildings by pious foundations began to be constructed even in the fırst years after its conquest. It is a pity that we were unable to preserve these historical and precious cultural traces and that we facilitated their disappearance and destroyed some of them without a twinge of regret. Works at the top of the list that suffered this tragic fate are bridges. Only the inscription of the Selçuk Hatun (Mihraplı) bridge dated 1465 has been preserved in a museum while the bridge itself has been destroyed; the Nilüfer bridge has also vanished. The Irgandi bridge was a rare instance of a bridge with wooden shop lining both sides of the bridge from olden times; after they were damaged by the Greek army in the War of Liberation, they were renovated in a very poor fashion. Though the Abdal bridge at the side of the İzmir highway has been restored, it has been left down below beside the modern bridge. One must now look for the last examples of the old Turkish bridges on byways outside the city limits. Of the other types of pious structures, the imaret, or soup kitchen, of Murad I has, lamentably; lost its original form and fallen into sad ruins. The Darüş-şifası, the truly oldest Ottoman hospital, which was built by Yıldırım Beyazıd was in a similar state until its recent renovation.

The hot spring waters especially peculiar to the Bursa region contributed to the development of the Turkish bath (hamam) and hot springs thermal bath architecture. At one time, the Turks were incredibly fond of public baths. The original foundations of thermal springs resorts at Bursa are from the Roman period and perhaps extend back to much earlier civilizations. They were rebuilt in the Turkish period and a number of other public baths were built in the city. In these thermal springs resorts and public baths, the character of the architectural traditions of the art of Turkish bath construction received inspiration from various circles; and one may determine and read the various stages in the development of experimentation in their search for the features of architectural traditions and their various types and innovations. The Orhan public bath, which was in use for a long time as a covered market, the ruined Tavukpazarı bath or the baths of İncirli, Perşembe and Yeşilcamii, the Eski thermal springs resort in Çekirge quarter and the Yeni thermal springs resort are some examples that can be noted of this kind of work. The Hacı Hamza bath in İznik and the Ulu bath, whose marvelous architecture is evident despite its advanced state of ruins may also be recalled.

Bursa was not only a political center a cultural center and a leading city of the state in the Turkish period, it also found opportunities for development as one of the great commercial centers. Besides being appropriate for fruit growing in the area, the raising of silk worms in conjunction with the founding of the silk industry were the primary factors in the growth of Bursa as a trading center. Conforming to the main principles of ancient Turkish urban planning in the city, the magnifıcent bedesten, or stronghold hall, of Yıldırım Beyazıd and the hans, or commercial buildings of caravansery type, such as Pirinç Han, Emir Han and the attractive Koza Han which has a small mosque in its courtyard, Fidan Han, Geyve Han and Arabacılar Han; besides the numerous hans, a number of closed market halls were also built starting in the very early period. In time, with the increase in the volume of trade, vacant areas were fılled with such markets as Uzunçarşı, İvaz Pasha market, Gelincik market and Sipahi market; the Bursa Grand Bazaar was created by an accretion of a number of market bedestens and hans and even by places of businesses occupying the street area. Restoration of this bazaar which underwent a great deal of damage due to a fıre in recent years, represented an attempt to recreate the original structure and renewal of the perimeter. The remains of the Bâlî Bey han in Bursa, half of which has disappeared, are still standing. Another industrial art that achieved renown in the environs of Bursa and which exhibited great growth in the sixteenth century and which produced the most magnifıcent works in Turkish art is the glazed tiles of İznik. How very sad that this branch of art that experienced such a brilliant beginning lasted for only a short time. İznik tile making, which attained an unequalled height of pertection in the sixteenth century, has disappeared without leaving a trace. Several caravanseries that were built to accommodate travelers on their way to the great centers of the Ottoman empire stand in a state of ruins as a reminder of an old civilization. Issız han situated near Ulubat represents such an example.

No remains of any kind of the early Ottoman palace are extant in this region. What is known of the early Turkish palace in Bursa is comprised of what a foreign traveler reported who visited here in 1432 when it was in a flourishing state. Among the works that have survived of stone and brick, the old houses built by residents of the area for their own use and which met their daily needs are beautiful examples of the Turkish aesthetic, which is now vanishing, and at the same time charming and attractive examples of strong traditions. How sad that one of the elegant examples of this minor art, which have been victims of the ravages of time along with our mistaken views, burnt down; this old residence was, for some reason, known as the House of Murad II (fıfteenth century), but which actually derived from the eighteenth century. This house, which provided a cool place for relaxation on the airy open hall, or hayat, had its rooms decorated with colored designs in a pleasurable scheme. Another example that soothes the eye, both from the perspective of decor and elegant construction, is the Şamaki house. Today, in Bursa and in most of the towns of the area and on streets that have retained their character houses belonging to the previous century are the last souvenirs of Turkish art bound to the old traditions. One of the most beautiful baths in a Turkish house is, without doubt, an example in İznik. For some reason this small work, which is called the bath of İsmail Bey, and whose interior decoration is unsurpassable, is, in fact, we believe a palace of the Candarlı family. The houses of our day that are unserviceable, disregard the terrain and climatic conditions and which, because of this, are lacking in comfort and bereft of pleasure and beauty. What a pity, concrete piles with colorless, spiritless facades have replaced them.

Bursa and environs, which possess elements that support its waters, greenness and natural beauties, occupy a place in the history of our civilization as a center where the masterworks of the most important phase of Turkish art are gathered...